Availability: Undetermined - Enquiries?

In the Field

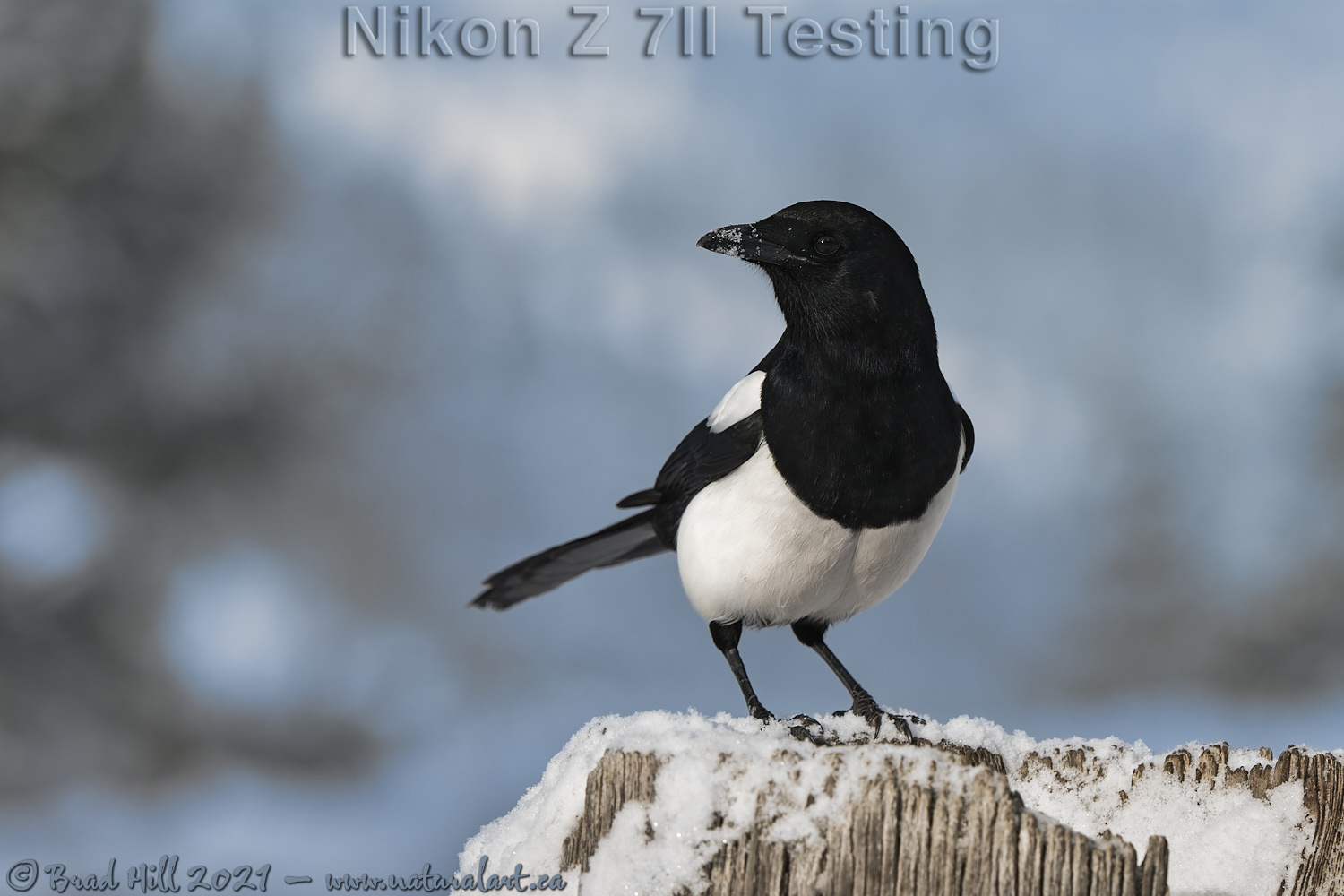

Z 7II Testing - Black-billed Magpie. Findlay Creek Region (East Kootenays), British Columbia, Canada. December 26, 2020.

This is another installment on my experiences with wildlife shooting using the Nikon Z 7II. But before I get into the technical topic associated with this image...a little about the subject matter of this shot...

Black-billed Magpies are strikingly marked members of the jay family, and certainly not what most would describe as "rare" birds in northwestern North America. But they do tend to associate strongly with human habitation, and as one who lives on an acreage away from other humans, it is very rare for a magpie to show up in our "yard". So when I was testing out my Nikon Z 7II for shooting wildlife I was thrilled to have this one unexpectedly make an appearance on the scene. And the reasons for my excitement went beyond having the opportunity to see (and photograph) a species that is poorly represented in my wildlife portfolio.

Dynamic Range (or DR) is a concept most serious digital photographers understand well and is generally thought to mean "the full brightness range of a scene that a camera can capture". If a modern digital camera can capture 14 stops of DR it means that the brightest part of the image can be over 8,000 times brighter than the darkest part (and can still be recorded by the camera) - which is pretty darned amazing. As an aside, most experts claim the human eye has a DR of about 11 or 12 stops...so it is arguable that the latest and best cameras (like the Nikon Z 7II) have a wider DR than our eye. In nature photography the genre of photographers that have the keenest interest in wide DR cameras are generally landscape shooters - and most wildlife shooters think about it less than the landscape shooters do.

But, there are instances where even if we (as wildlife photographers) limit our attention to the subject alone (and ignore what's going on in the rest of the frame) that shooting with a camera with a wide DR is advantageous. Some extreme examples would include working with Giant Pandas, photographing breaching Killer Whales, or even if working up close and personal with an adult Bald Eagle (yeah, yeah...I know...these aren't necessarily everyday occurrences for most folks). But...how about a fairly tight shot of a Black-billed Magpie in direct sunlight? Yep, that's a great example of an animal with exceptionally dark (i.e., black) regions and brilliantly white regions...and one that puts huge demands on the DR of a camera.

So...when THIS magpie showed up at our cabin in late December of 2020 I was thrilled to see how my shiny new Z 7II would handle the situation. And, I was pleased to find that the full brightness range of the magpie - from its darkest "dark-on-black" tones through to its brightest "light-on-white" tones - were all successfully captured without any blacks blocking up or any highlights being blown.

I'm not going to claim for even a second that this extreme DR recording ability is needed for the bulk of wildlife photography. But, if you choose to use your Z 7II for wildlife shooting (and I am finding it to be a very versatile wildlife camera myself) it's nice to know that you shouldn't ever be tripped up by it not being able to handle the DR of your scene!

Here's a larger version (4800 pixel) of this boldly patterned member of the jay family for your perusal:

• Z 7II Testing - Black-billed Magpie: Download 4800 pixel image (JPEG: 2.5 MB)

ADDITIONAL NOTES:

1. This image - in all resolutions - is protected by copyright. I'm fine with personal uses of them (including use as desktop backgrounds or screensavers on your own computer), but unauthorized commercial use of the image is prohibited by law. Thanks in advance for respecting my copyright!

2. Like all wildlife photographs on this website, this image was captured following the strict ethical guidelines described in The Wildlife FIRST! Principles of Photographer Conduct. I encourage all wildlife photographers to always put the welfare of their subjects above the value of their photographs.

Behind the Camera

Z 7II Testing - Black-billed Magpie. Findlay Creek Region (East Kootenays), British Columbia, Canada. December 26, 2020.

Digital Capture; Compressed RAW (NEF) 14-bit format; ISO 80.

Nikon Z 7II paired with Nikkor 180-400mm f4E @ 240mm. Supported on Jobu Killarney tripod with Jobu HDMkIV gimbal head. VR on and in Sport mode. Single Point Area AF area mode.

1/250s @ f7.1; +0.33 stop exposure compensation from matrix-metered exposure setting.

At the Computer

Z 7II Testing - Black-billed Magpie. Findlay Creek Region (East Kootenays), British Columbia, Canada. December 26, 2020.

RAW Conversion to 16-bit PSD file (and JPEG files for web use), including all global and selective adjustments, using Phase One's Capture One Pro 21. Selective local adjustments performed using Capture One Pro's layers and masking tools. In this case selective adjustments were made on 8 separate layers and included one or more tweaks to highlights, blacks, clarity, contrast (via curves), and color balance.

Photoshop modifications were limited to the insertion of the watermark and/or text.

Conservation

Z 7II Testing - Black-billed Magpie. Findlay Creek Region (East Kootenays), British Columbia, Canada. December 26, 2020.

Species Status in Canada*: This species is not designated as at risk.

The Black-billed Magpie (Pica hudsonia) is a boldly patterned medium-sized member of the family Corvidae (crows and jays). Adults are largely black, with contrasting white scapulars, a white belly, and iridescent blue-green wings and tail.

In North America the Black-billed Magpie is found across a wide band in the northwest region of the continent and their general distribution in the west correlates well with cold-type, dry-steppe climate.

Numbers of Black-billed Magpies appear relatively stable in North America. Sadly, up to about the middle of the twentieth century they were persecuted as "vermin" and to some extent this prejudice still exists among farmers and ranchers. However, at this point there is no immediate threat to Magpie populations from human activities.

*as determined by COSEWIC: The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada